Accountability Round Table continues to pursue better resourcing of the Office of the Australian Information Commissioner. Following the appointment of Australia’s new Attorney General, The Hon Christian Porter, Accountability Round Table sent the following letter and explanatory attachment to him on Sunday 28th January, explaining the obligations the Australian Government has to proper resourcing of the OAIC,

Below you can read;

The covering letter

The attachment discussing the funding and performance of the OAIC.

Appendix A. NAP Commitments expressly involving the OAIC

Appendix B. Australia’s OGP Commitments

Christian Porter’s reply to this letter can be found here

The Hon Christian Porter MP.

Attorney-General

Parliament House

Canberra ACT 2600

Dear Attorney-General

Australia’s participation as a member of the Open Government Partnership (OGP) is potentially one of the most far-reaching initiatives of the Turnbull Government.

The Accountability Round Table is a strong supporter of the OGP and the associated National Action Plan (NAP) Commitments, as indicated to predecessor.

Your Department (AGD) and statutory agencies for which your Department is responsible have major roles in fulfilment of several of these NAP Commitments. It is important to the success of these Commitments that AGD and those statutory agencies have the support and resources necessary to execute their roles on behalf of the Government and the Australian people.

In particular, it is essential that the Office of the Australian Information Commissioner (OAIC) has the capacities to discharge its statutory obligations and tasks which now include 9 NAP Commitments (see Attachment – Appendix A)

The recent ANAO’s Performance Audit of the OAIC, together with the OAIC 2016 – 17 Annual Report and the OAIC’s first Corporate Plan, reveal concerning assessments of the adequacy of the resourcing and, where it has been provided, the work performed and, the quality of the performance of the work, discussed below.

A. The level of funding the Privacy and FOI functions of the OAIC

Since 2014 – 15, the funding to discharge FOI functions has been halved from $5 million to $2 to $2.5 million with overall funding for FOI and Privacy functions ranging between $9 million-$11 million.

The limited funding appears to have been diverted from FOI functions predominantly to the Privacy functions e.g. enabling Privacy regulatory action and, publication of the Regulatory Action Plan and a Guide (see Attachment paras 1 and 2.).

B. The performance of the FOI functions

The ANAO Report did not review the performance of the OAIC in all of its statutory FOI function areas. But the Report indicates that the OAIC has not been addressing matters within all those areas.

The OAIC’s FOI functions have been limited by its FOI resources to the handling of FOI merits reviews and complaints. The demand for those functions continue to increase. (See Attachment paras 3.1-3.5)

C. Quality of performance of particular functions

The ANAO Report noted unsatisfactory performance of two major statutory OAIC FOI functions – Commissioner initiated investigation reports and surveys of the Information Publication Scheme (IPS) compliance (a system intended to provide and underpin a pro-disclosure of information self-driven culture). (Attachment paras 4.1 to 4.3).

The ANAO Report was critical of

- the absence of any system for verification of statistical information from entities and the failure to monitor the operation of the IPS (the last such review occurring in May 2016); and

- the use of section 54W of the FOI Act “as a workload management tool” (Attachment paras 4.1 to 4.3).

D. The operation of the statutory three Commissioner structure

This matter was not reviewed by the ANAO Report but is a very serious issue adversely affecting the operations of the OAIC.

The three statutory Commissioner roles are presently conducted by the Privacy Commissioner who is not qualified to be appointed to one of them, the FOI Commissioner position, lacking the statutory required legal qualification. (Attachment para 5)

A consequence of the above failures and actions is that the Government (and therefore Australia) has been in breach of significant express OGP Commitments for several years (Attachment Appendix B). It has also been in breach of the long standing, but too often forgotten, public office public trust principle. (Attachment para 6).

At the heart of the breaches is the failure of the Government to ensure adequate resourcing of the OAIC to enable it to discharge its statutory FOI functions.

Civil Society took these issues up in the NAP process resulting in the following express commitment being included in the NAP –

“The Government is committed to ensuring the adequate resourcing of the OAIC to discharge its statutory functions and provided funding for this purpose over the next four years in the 2016 – 17 Budget” ………(NAP p. 36).

It should be noted that the Government has not claimed that adequate resourcing for the stated purpose had been provided for the 2016 – 17 Budget nor did it say that it would be provided in the next Budget – and it wasn’t.

Thus, the actual Budget provision is in breach of this specific OGP/NAP commitment. We are still awaiting an indication of the action proposed to address all the outstanding commitments.

In Budgetary terms, the action required is trifling. At the same time, however, there is yet to be a public explanation of the reasons for not providing adequate resourcing in the last two Budgets for the OAIC.

Urgent action is needed. We seek your assurance, as the Minister of the NAP lead agency for this OGP Commitment, that

- the OAIC will be supported and adequately resourced in the next Budget to ensure that it can discharge its statutory functions including its NAP tasks, and that

- proposals will be published by the Government for discussion and consultation with civil society before the end of February.

The Accountability Round Table stands ready to participate in such discussions and consultations.

Yours Faithfully

Hon. Tim Smith QC

Chair, Accountability Round Table

Attachment – Relevant Background, evidence and analysis.

- The level of funding of the OAIC

The ANAO’s Performance Audit of the OAIC explored this issue with the assistance of the OAIC. It published the following table:

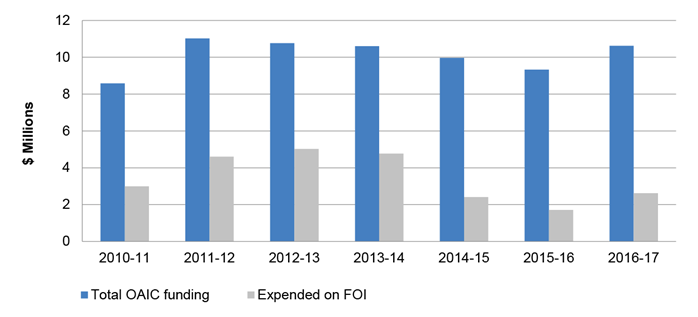

Figure 1.6: Funding expended by OAIC on freedom of information functions, 2010–11 to 2016–17

Source: ANAO (Note from the introductory statement ( para 1.19) – “When the Bill to disband the OAIC was not considered by the Senate before the due date of 1 January 2015, partial funding was reallocated every six months to enable the office to continue to undertake a streamlined IC review function from the Sydney office.”)

It shows that the funding for the FOI functions was effectively halved in the 2014 – 15 Budget and remains so; in particular

- prior to the OAIC Budget of 2014 – 15 Budget, an average funding per annum of $ 5 million (45%) was provided for the FOI functions and $11 million for all functions, and

- in that Budget, and subsequently, funding for the FOI functions ranged from under $2 million towards $2.5 Million (between 21% and 24%) and approximately $9 million-$11 million for all functions.

Thus, in the 2016 – 17 and 2017-18 Federal Budgets, the reality has been that

- the funding level for the FOI functions was not “mostly” restored -it was not restored at all, and

- the OAIC’s FOI financial resources were halved and have remained so.

- Where has the bulk of the funding been applied since the 2014 – 15 Budget?

The ANAO Report records that the OAIC commented that, with the period of its attempted disbanding behind it,

“the OAIC is pursuing all its statutory FOI regulatory activity, taking into account our resourcing and balancing our priorities across all of our statutory functions” (Conclusion “Summary and Recommendations” -30)

In other words, the OAIC has not given up on all its statutory obligations but its resources are limited, and a balance has to be struck between its resources and its statutory functions. The above ANAO Report Table confirms that this is a very real and significant issue for the performance of all the OAIC’s statutory functions – but mainly those that are FOI functions.

The available evidence points to the funding having been spent primarily on the Privacy functions, not the FOI functions.

(a) An important statutory function is Commissioner Initiated Investigations (CIS). The OAIC website lists the investigations undertaken. They relate to Privacy matters. See consequential determinations (See also the OAIC Annual Report 2016-7 p 43ff –

The website also records CIS investigations into FOI matters – – 3 in all, in 2012 and 2014, none since the 2014-15 Budget..

(b) The OAIC Annual Report 2016 – 17 includes detailed reports on the OAIC’s performance of its responsibilities in both the Privacy and FOI fields. The Privacy Performance Chapter (which included independent Commissioner Investigations) is 28 pages and that for FOI, 12.

The Report also refers to the OAIC’s engagement with one of the major statutory FOI and Privacy functions – the Information Publication System (IPS). The Report, however, appears to focus on Privacy matters.

(c) The ANAO Report (CH.4 Conclusion) also records the failure of the OAIC in 2016 to conduct the scheduled review of the IPS on FOI matters (scheme intended to provide and underpin a pro–disclosure of information self-driven culture)

It also reports (fn33) concerning the OAIC’s role as the regulator for the Privacy Act 1988, that the OAIC publishes a detailed Privacy regulatory action policy and a Guide to privacy regulatory action”. It criticises the OAIC for not doing the same for the FOI functions

The present funding priorities appear to be restricting the OAIC to FOI merits reviews and complaints. This appears to be confirmed by the reference in the 19 October letter received by ART from the then Attorney-General about the moving of $ 0.5 million from the AAT to the OAIC to help it cope with the growing workload of FOI merits reviews and complaints.

This is a move, however, that will reduce the AAT’s ability to address its FOI responsibilities. Why was that amount not taken from the funding provided for the Privacy functions of the OAIC – approximately $8 million? (See the Table) Is it because it is set aside for Privacy functions and Privacy functions are to have priority in funding over FOI funding issues? Why is the Privacy role regarded as more significant?

Is there a formal structure in place within the OAIC or elsewhere to determine the proportion of the funding to be spent on Privacy matters and on FOI matters?

- The performance of the FOI functions[1]

3.1 The ANAO’s stated objectives

The ANAO set itself the task of assessing “the effectiveness and efficiency of the OAIC in providing “guidance and assistance to entities and monitoring compliance with the FOI Act” (Summary, paras 2-3)

3.2 ANAO questions/OAIC responses

The ANAO reported that it asked the OAIC whether there were tasks or functions that it was not now performing. It responded: (2.30)

“There are no functions that the OAIC is not now performing. The OAIC prioritises its activities within the resources available to it, to best deliver all its functions. As such, our ability to undertake intensive work, for example, around the IPS scheme and some discretionary activities such as Commissioner initiated investigations may not be as feasible as in previous years, but we still plan to undertake some limited work in these areas.”

In other words, there are statutory functions on the list to be performed and they are “on its list of functions to be performed when it can”, including the IPS function.

3.3 ANAO further exploration. The ANAO explored the issues with the OAIC, in particular, re Section 8 of the AIC Act which imposes a large number of FOI’s functions on the OAIC (see fn 2). It focused on Section 8(g) of that Act which gives OAIC the function of ‘monitoring, investigating and reporting on the compliance by agencies with the Freedom of Information Act 1982’.

It sought examples from the OAIC of its performance of this function. The following were proffered (2.31-32)

- Annual reports, (to publish statistics and other information received from other entities and some commentary)

- publication of statistics (compilation of data self-reported by entities),

- Commissioner initiated investigation reports (one in 2012 and one in 2014 – at the request of Department of Immigration and Citizenship and Department of Human Services),

- specific compliance reports e.g. survey of IPS compliance (conducted in 2012 by entities self-assessment) and

- submissions to inquiries (the Hawke enquiry in December 2012

The first two are presently conducted. The third and fourth have not been performed since the 2014 – 15 Budget.

3.4 FOI applications – Merit reviews

The OAIC reported to the ANAO that it had met its performance target for merit review of entity decisions for the first time in 2015–16. (see “Summary and recommendations; conclusions” -para7)

The ANAO noted (ibid) that –

- the time required to conduct a merit review varies substantially, with the elapsed time for decisions reported by OAIC in 2015–16 ranging from 81 to 1228 days (average of 372 days) (ibid) and

- the number of exemptions from release being claimed by all entities across the Commonwealth has increased by 68.4 per cent over the last five years (ibid – 10);

thus, a significant increase in exemptions claims in recent years and long times for the resolution of reviews by the OAIC?

3.5 ANAO conclusions re OAIC functions performed

The OAIC website contains a large amount of guidance and information material for applicants and entities and effectively meets the obligation under s 93A of the FOI Act to ‘issue guidelines for the purposes of the Act’. (Supporting finding, Conclusion – 15)

The ANAO noted that

- the OAIC published a wide range of useful guidance and information material for entities and FOI applicants (Conclusion, 6) –

- “the OAIC’s regulatory activity since 2012 has been limited to its analysis and commentary on entities’ self-reported statistics.” (Does OAIC fulfil its regulatory role – 2.35).

- OAIC …does not have a statement of its regulatory approach in relation to FOI.” (2.34).

The OAIC has responded by including in its 2017 – 18 Corporate Plan a commitment to Fapproach with respect to our full range of FOI functions.” (2017 – 18 Corporate Plan )

The ANAO also identified (“Does OAIC fulfil its regulatory role” – table 2.2, 2.32) some major FOI functions that have not been performed by the OAIC in recent years;

- the FOI functions of initiating investigations – not performed since 2014 and

- surveying the Information Publishing System (IPS) had not taken place since 2012.

| 4. Quality of performance of particular functions |

4.1 Provision of statistics to the OAIC about FOI activity.

Returns are required quarterly and annually from entities and are reported through a portal. The OAIC provides entities with guides to assist them in the submission process. The ANAO reported – “although OAIC advised that it risk manages the collection of statistics, it undertakes very limited quality assurance of their accuracy” (Supporting Findings –

“2.26 The ANAO observed errors in the reported information, such as detailed breakdowns of statistics being inconsistent with totals. The ANAO asked OAIC whether it undertook any quality assurance or verification of the data input to the portal be entities.

The OAIC responded: One does undertake activity to risk manage the statistical collection to ensure as accurate statistics as possible are inputted by agencies but given the number of agencies and the number of data points collected and resources available to the OAIC it is not possible to check every single data point entry each quarter and in the annual reports. The general trends observed from the statistical collection are very useful and a significant input to understanding the how the FOI Act is being applied by agencies and ministers.

OAIC does undertake activity to risk manage the statistical collection to ensure as accurate statistics as possible are inputted by agencies but given the number of agencies and the number of data points collected and the resources available to the OAIC it is not possible to check every single data point entry each quarter and in the annual reports. General trends observed from the statistical collection are very useful and a significant input to understanding how the FOI act is being applied by agencies and Ministers¶.

The ANAO further reported

2.27 FOI statistics have been reported to Parliament every year since 1998–99. The reports to Parliament have included detailed analysis and commentary on trends and issues.The reports also identify those entities which are not meeting statutory benchmarks such as processing FOI applications within the statutory time period. Such information is useful for Parliament and the ‘FOI community’.

As to the reliability of the statistics -,

2.28…… Its reliability depends upon the accuracy of the raw data input from entities. There would be benefit in OAIC considering developing an approach to verifying the quality of data input.

It also referred (2.34) to a statement in the OAIC’s 2016–17 Corporate Plan and its 2015–16 Annual Report that the OAIC is ‘successful when we undertake FOI regulatory functions under the FOI Act in an efficient and timely manner’. The ANAO noted that, OAIC’s regulatory activity since 2012 has been limited to its analysis and commentary on entities’ self-reported statistics.

4.2 The Information Publication Scheme (IPS).

As noted, the IPS (s 8-9A;) has a very important role to play in providing and underpinning a pro-disclosure culture across government, and transforming the freedom of information framework from one that is reactive to individual requests for documents, to one that also relies on agency – driven publication of information”.

These are also objectives at the heart of the OGP initiative (see below Appendix B)

The OAIC and the entities are also obliged by statute to review the operation of the IPS Scheme every five years. (FOI Act S 9). The first review was due on May 2016. The ANAO reviewed the performance of the OAIC and the 3 entities and found that none had met that statutory requirement.

The ANAO also noted that the last OAIC compliance report concerning a survey of IPS compliance occurred in 2012; (“Does OAIC fulfil its regulatory role?” – (2.32 table 2.2)).

Considering the demands of the FOI reviews and complaints functions, its lack of funding and having only one Commissioner appointed to discharge the functions of 3 Commissioners, it is hardly surprising that the OAIC has not engaged in monitoring the IFP scheme and, as a result, it is not surprising that entities have failed to discharge their responsibilities.

4.3 FOI merits reviews – the discretion not to review; s 54WB – lack of funds?

The ANAO did not review complaints about the FOI review process (Audit Scope -1.24). It did however, review the “streamlining” of the review decisions processes. In particular, the ANAO (2.15) noticed that the use, between 2012 – 13 and 2013 – 14 of section 54W to decline to consider review applications had doubled from 149 to 300.

The ANAO Report queried the soundness of the approach. It “sought comment from OAIC about whether it was aware of any reason for this increase”. OAIC advised that it ‘can only speculate that, given the backlog of matters at that time, a stronger line was taken by the decision-makers on whether the review was lacking substance’.

The ANAO commented: “2.17 While the ANAO notes OAIC’s explanation, it considers that the exercise of a discretion not to review an application should be based on the merits of the application rather than the discretion being used as a workload management tool.” This is particularly relevant to the particular trend followed of relying on s54W(b) which provides –

“The Information Commissioner may decide not to undertake an IC review, or not to continue to undertake an IC review, if…….(b) the Information Commissioner is satisfied that the interests of the administration of this Act make it desirable that the IC reviewable decision be considered by the Tribunal” (i.e. the AAT).

The consequence of exercising section 54W (b) is that the OAIC review does not take place and whether or not it goes to the AAT will be a matter for the parties. There is also a charge to be met at the AAT by the applicant.

One could understand the OAIC exercising that power if, for example, there was uncertainty in the interpretation of the legislation and a ruling by the AAT would be of great assistance to the administration of the Act. But here the trigger for action appears to have been the consequence of inadequate funding of the system and the difficulty, as a result for the OAIC, created by the Parliament, to discharge its responsibilities under the legislation within a reasonable time. Can it be desirable in the interests of the administration of the Act for the Information Commissioner to decline to deal with the matter and pass it effectively on to the AAT when its funding has been reduced by $.5 million?

Do we come back again to the need to seriously examine the financial needs of this important statutory body, the OAIC, to enable it to perform its statutory functions. The cost to the budget sums will be minimal but the benefits to good government and the community significant i.e. there would be a strong positive cost benefit.

- The operation of the statutory three Commissioner structure.

The arrangement originally legislated by the Parliament requires an FOI Commissioner and a Privacy Commissioner working with the lead Commissioner, the Information Commissioner. The legislation requires that the FOI Commissioner have legal qualifications.

The present arrangement could not be more different with one person performing all three Commissioner roles and their functions even though lacking the legal qualification to be appointed the FOI Commissioner but being able to exercise them as the Information Commissioner. Serious questions have been raised about whether such arrangements place the Executive Government in breach of its obligations under section 61 of the Constitution and the constitutional principles of the separation of powers and the rule of law. (e.g. Dowd 2015).

The original statutory structure of three qualified Commissioners provided a best practice option for the challenge of leading and operating the proposed OAIC and addressing the competing challenges of rights to privacy and right to information. We no longer have that benefit and we have not for some three years. It has been replaced, by Executive action, with a seriously underfunded improvisation. In addition, as a result of Executive funding decisions, the Privacy function aspects appear to have been given de facto priority over the FOI functions. The practical result of the withdrawal of funds from the FOI aspects has been to limit the FOI functions to the reviews of FOI applications and complaints about the system. In doing so, the practical outcome has been that we have gone back to the original reactive system as opposed to the OAIC proactive system that the Parliament enacted in 2010 – 11. As a result Government has abandoned a best practice system, notwithstanding the Government’s and our Nation’s public commitments to the pursuit of best practice as a member nation of the OGP.

Has Government also lost sight of its importance for the whole community? As Dr Cameron, one of the founders of the OGP said

“..an open, inclusive economic system backed by open, political inclusive institutions – that is the best guarantor of success” .

- Relevant concerns to be borne in mind?

(a) Public Office as a Public Trust.

Has Government lost sight of this long standing ethical and leading principle? As explained by Sir Gerard Brennan, former Chief Justice of the High Court:

“It has long been established legal principle that a member of Parliament holds “a fiduciary relation towards the public” (3) and “undertakes and has imposed upon him a public duty and a public trust”(4). The duties of a public trustee are not identical with the duties of a private trustee but there is an analogous limitation imposed on the conduct of the trustee in both categories. The limitation demands that all decisions and exercises of power be taken in the interests of the beneficiaries and that duty cannot be subordinated to, or qualified by the interests of the trustee. As Rich J said (5):

“Members of Parliament are donees of certain powers and discretions entrusted to them on behalf of the community, and they must be free to exercise these powers and discretions in the interests of the public unfettered by considerations of personal gain or profit”.

(b) Budgetary Concerns?

The abovementioned 11th October 2017 letter of the former Attorney-General warns that “any proposals to increase OAIC funding will need to be considered in the context of the current fiscal environment and other competing priorities as part of the 2018 – 19 Budget process.”

It is presumably always relevant to consider possible “fiscal environment and other competing priorities” in situations where budget expenditure is being considered. In the present instance, they are presumably to be weighed with the benefits of adequately resourcing the OAIC.

Fortunately, the situation appears to be one where, with a very minimal budgetary expenditure,

- citizens’ rights to privacy and access to government information will have a best practice system to protect, secure and serve them and –

- Australia will have “an open, inclusive economic system backed by open, political inclusive institutions – that is the best guarantor of success” –

There is a further issue that has not been discussed. The 11th October 2017 letter of the former Attorney-General states that the Government “recognises the importance of the OAIC in discharging Australia’s responsibilities under the Open Government Partnership” but says nothing about

- the reality that organisations like the OAIC have been called upon to add significantly to their previous existing functions or

- the need to adequately resource them so that they can discharge those functions without setting back their existing functions.

The OAIC is involved in 9 of the NAP commitments and the lead agency in two of them (commitments 2.2 and 3.2 – (see Appendix A). They all concern aspects of open and accountable government and the statutory functions of the OAIC. The OAIC Corporate Plan does not appear to have attempted to cover those matters.

- A first step towards addressing the issues?

The Rule of Law commitments of the A.G. Department have been strongly stated in its Corporate Plan 2017. The Corporate Plan acknowledges –

- its “primary responsibility for supporting the Australian Government in protecting and promoting the rule of law” and that the “rule of law underpins the way Australian society is governed”.

- the ways it upholds the rule of law in its daily work including that “the laws are publicly made and the community is able to participate in the lawmaking process”.

It goes on to state –

“We support the Australian government in being accountable for actions, taking rational decisions and protecting human rights”.

The FOI system, including particularly the OAIC, are central to these objectives.

The establishment of the OAIC in 2010/11 promoted and protected the rule of law. Executive Government action in and since the 2014 – 15 Budget, however, has significantly limited its ability to do so.

Concerns had been raised publicly including by a former Attorney-General, the Hon John Dowd, in his role as the President of the Australian section of the International Commission of Jurists (ICJ).

Do the recently published Rule of Law commitments reflect recognition and acceptance of the need to act to enable the FOI system, including the OAIC, to protect and promote the Rule of Law for the Commonwealth of Australia?

Conclusion

The issue of the resourcing of the OAIC has been on the table for some time. We thought it was recognised in the commitment made in Commitment 3.1 – “to ensuring adequate resources for the discharge of the OAIC’s statutory functions ——-.” A year has now gone by since that commitment was made during which the Government failed to honour it in the 2017 – 18 Budget.

Bearing in mind the intensity of the political world in the last 12 months, it would not be surprising if this issue had simply been overlooked.

But the Attorney-General’s Department is the lead agency for Commitment 3.1.

We do not seek an explanation for what has failed to occur. We seek your assurance, as the Minister responsible, that in the implementation process of the first NAP, the Government will join with those involved in the Open Government Forum to honour the letter and the spirit of the resourcing commitment included in Commitment 3.1 together with Government’s overarching OGP commitments to secure adequate resourcing for the OAIC in both its Privacy and FOI functions including the restoration of the appointment of three lawfully qualified Commissioners under the legislation. By doing so the public office public trust principle will be respected and applied.

Hon. Tim Smith QC

Chair ART

Return to top

Appendix A; NAP Commitments expressly involving the OAIC.

1.2 Beneficial Ownership Transparency;

With Treasury as the lead agency, the OAIC is one of four Commonwealth Government Actors including Attorney General’s Department and the balance comprise all state and territory governments

2.1 Release high-value datasets and enable data driven innovation and enable data-driven innovation

O AIC included in government actors with Commonwealth government agencies and state, territory and local governments.

2.2 Build and maintain public trust to address concerns about data sharing and release

OAIC a lead agency with PM and C and Australian Bureau of Statistics with Govt actors comprising 12 government departments and agencies and state and territory governments

3.1 Information Management and access laws for the 21st century

OAIC is a government actor with the National Archives of Australia and Prime Minister and Cabinet – lead agency Attorney-General’s Department

3.2 Understand the Use of Freedom of Information

The OAIC is a lead agency together with all other Australian Information Commissioners and Ombudsmen and the only “Government Actor”

3.3 Improve discoverability and accessibility of Government Data and Information.

The lead agencies are PM and C, Department of Finance, National archives of Australia and Department of Environment and Energy¶. The government actors comprise all Commonwealth entities and will therefore include the OAIC.

4.3 Open Contracting

The lead agency is the Department of Finance. The government actors are all Commonwealth entities and therefore include the OAIC

5.1 Delivery of Australia’s Open Government National Action Plan

The lead agency is the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet and all Commonwealth entities are the government actors presumably including the O AIC.

5.2 Enhance public participation in government decision-making

The lead agency is the Department of Industry, Innovation and science. The government actors ‘s comprise all Commonwealth entities and therefore include the OAIC – and specifically includes the Australian Charities and not-for-profits Commissions. Australian charities.

Appendix B. Australia’s OGP Commitments .

Australia’s specific OGP commitments as a participating member of the OGP, include

- “to consistently and continually advance open government for the well-being of their citizens.” (p 3 of the Articles of Governance)

- “…promoting increased access to information and disclosure about governmental activities at every level of government.” (p 20)

- increasing our efforts to systematically collect and publish data on government spending and performance for essential public services and activities” (ibid)

- providing access to effective remedies when information or the corresponding records are improperly withheld, including through effective oversight of the recourse process (p 20.

- creating mechanisms to enable greater collaboration between governments and civil society organisations and businesses” (p21)

- “to lead by example and contribute to advancing open government in other countries by sharing best practices and expertise…” (P 22)

Have we been, and are we now, honouring these commitments? And are we not required as a participating nation in the OGP to “Make concrete commitments, as part of a country action plan, that are ambitious and go beyond a country’s current practice” – “OGP Articles of Governance”, p.3)

[1] Links to the Statutory FOI functions provisions: Freedom of Information Act 1982. Part 11, the Information Publication Scheme, s 7A-10B, available at http://www6.austlii.edu.au/cgi-bin/viewdb/au/legis/cth/consol_act/foia1982222/ and AIC Act s8 and the sections of the FOI Act 1982 there named – ss 8 E, 8F, 90, 3A, 30, 31, 6, available at http://www8.austlii.edu.au/cgi-bin/viewdb/au/legis/cth/consol_act/aica2010390/